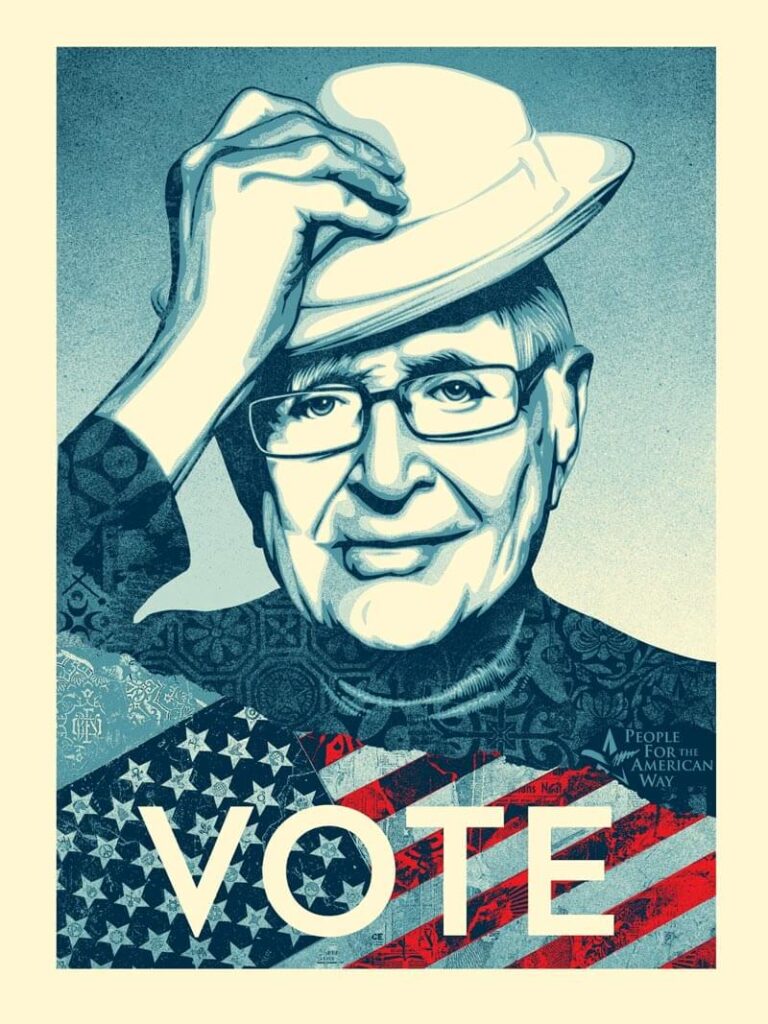

Courtesy of People For The American Way

Illustration courtesy of Shepard Fairey/ObeyGiant.com

Photo reference by Peter Yang/AUGUST

Honoring Norman Lear’s Legacy in Comedy and Civic Engagement

2024 marks the first modern election cycle absent the passionate voice of Norman Lear, the legendary comedy producer and writer who dedicated his life’s work to championing your right to equal participation in our democratic process — starting with your vote.

“The right to vote is foundational. It is at the heart of everything I have fought for in war and in peacetime. Protecting voting rights should not be today’s struggle. But it is. And that means it is our struggle, yours and mine, for as long as we have breath and strength.”

– Norman Lear

Before political humor was a mainstay of contemporary American entertainment, Norman Lear’s body of work proved that political discourse not only had a place in popular culture, but that incisive, intelligent comedy could engage vast, dispersed, and diverse audiences of everyday people in impactful conversations about the democratic process and each of our roles within it.

The groundbreaking sitcoms that he created, including All In the Family, Maude, The Jeffersons, Good Times, One Day At a Time, and Sanford and Son, not only entertained 120 million Americans each week at the height of their extraordinary popularity, but put forth a vision for how dinner table debates, neighborhood organizing, and showing up at a local polling place were the accessible — and meaningful — bedrock of American democracy.

Choose a Clip

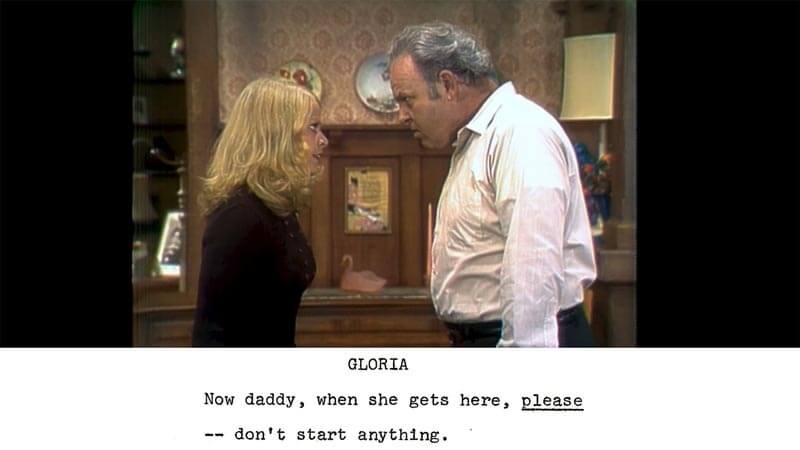

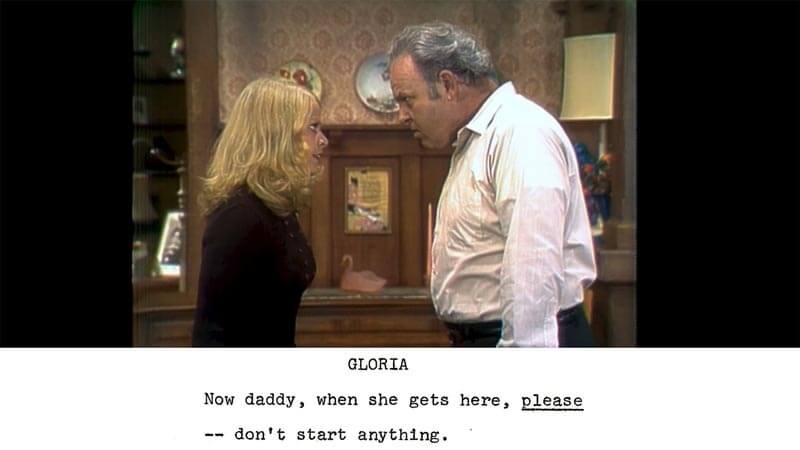

All In the Family, “The Election Story,” October 30, 1971 – 1

Much of All in the Family‘s narrative propulsion stems from a deep political rift that divides the Bunker household: Archie is a confident conservative, his daughter and son-in-law are outspoken liberals, and his wife, Edith, quietly attempts impartiality. Like many American families, the Bunkers find themselves clashing on any number of issues due to generational differences, gender differences, educational levels, and attitudes borne of disparate life experiences. In this episode, Archie balks when Gloria invites liberal candidate Claire Packer into his home, but Gloria turns the tables when she chastises her father for not actually exercising his right to vote. As was explained in an on-screen disclaimer before the earliest national broadcasts of All in the Family, Lear’s charge with this series was to use humor to deconstruct the complexities of Archie Bunker’s attitudes and opinions: “By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show—in a mature fashion—just how absurd they are.”

All in the Family (1971-1979, CBS) starred Carroll O’Connor as Archie Bunker, an irascible, opinionated blue-collar conservative who lords over a home shared with his long-suffering wife, Edith (Jean Stapleton), daughter (Sally Struthers), and outspoken liberal son-in-law “Meathead” (Rob Reiner). The show won 22 Emmy awards and is among the most influential comedy series of all time, infusing network television with realism, topicality, and controversy that would alter the medium’s course.

All In the Family, “The Election Story”

Original air date: October 30, 1971

Written by Michael Ross and Bernie West

Directed by John Rich

Featuring Carroll O’Connor, Jean Stapleton, Sally Struthers and Rob Reiner

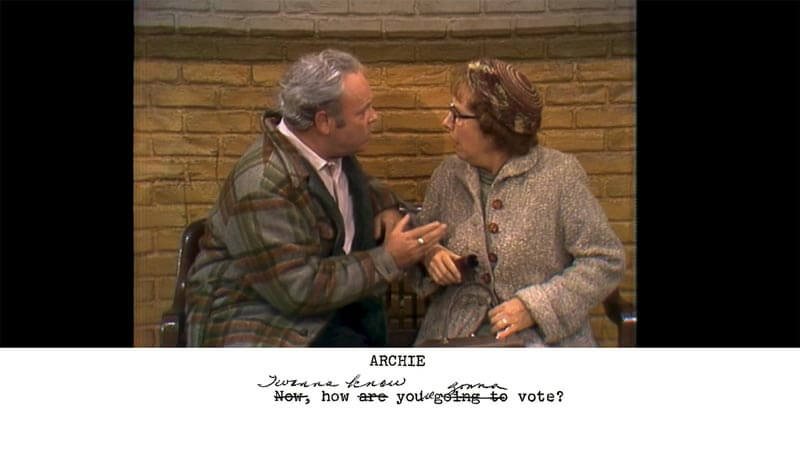

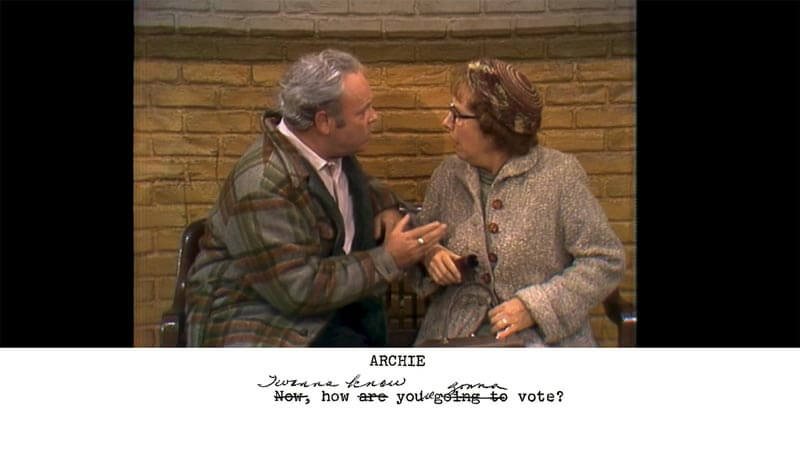

All In the Family, “The Election Story,” October 30, 1971 – 2

While most sitcoms find narrative closure in a neat wrap-up before the end credits roll, Lear’s shows were comfortable with unsettled issues, characters who wavered, and conflicts that didn’t lead to resolutions. In this episode, Archie confidently spouts political opinions but is chagrined when he arrives at his neighborhood polling place and finds himself unregistered…and therefore ineligible to vote. With characteristic arrogance, he attempts to persuade Edith to cast her vote on his behalf, but she staunchly upholds her right to equal participation and casts her vote for the opposition. Archie slumps in silent humiliation as the episode fades, realizing the futility of soliloquizing about politics without actually participating in the democratic process.

All in the Family (1971-1979, CBS) starred Carroll O’Connor as Archie Bunker, an irascible, opinionated blue-collar conservative who lords over a home shared with his long-suffering wife, Edith (Jean Stapleton), daughter (Sally Struthers), and outspoken liberal son-in-law “Meathead” (Rob Reiner). The show won 22 Emmy awards and is among the most influential comedy series of all time, infusing network television with realism, topicality, and controversy that would alter the medium’s course.

All In the Family, “The Election Story”

Original air date: October 30, 1971

Written by Michael Ross and Bernie West

Directed by John Rich

Featuring Carroll O’Connor, Jean Stapleton, Sally Struthers and Rob Reiner

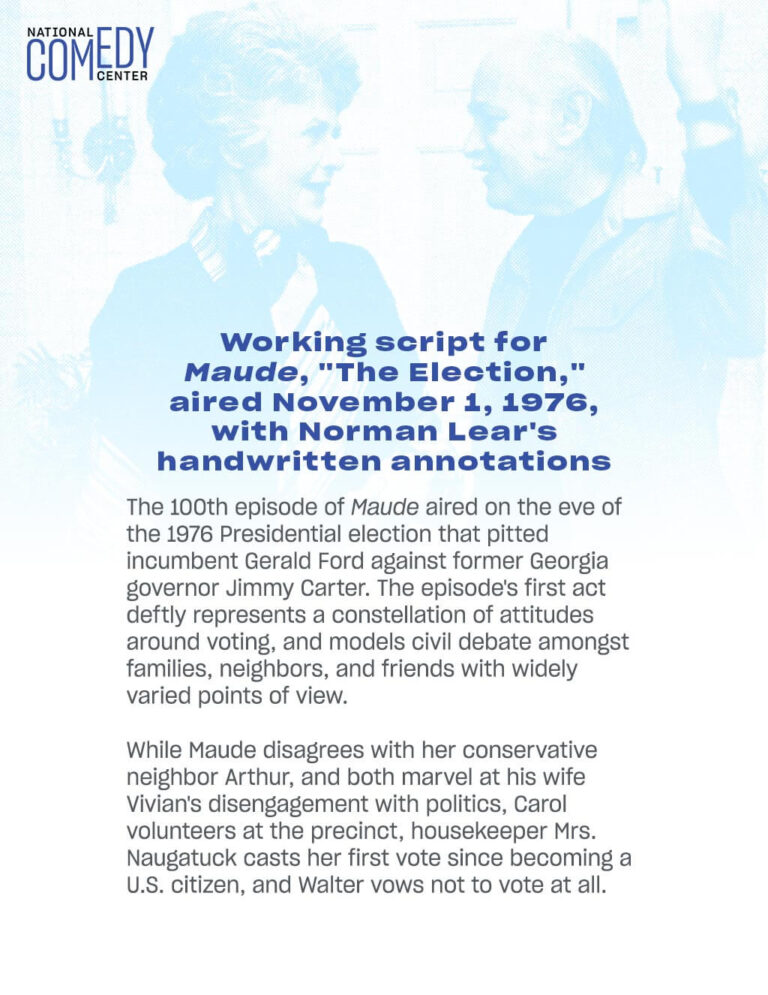

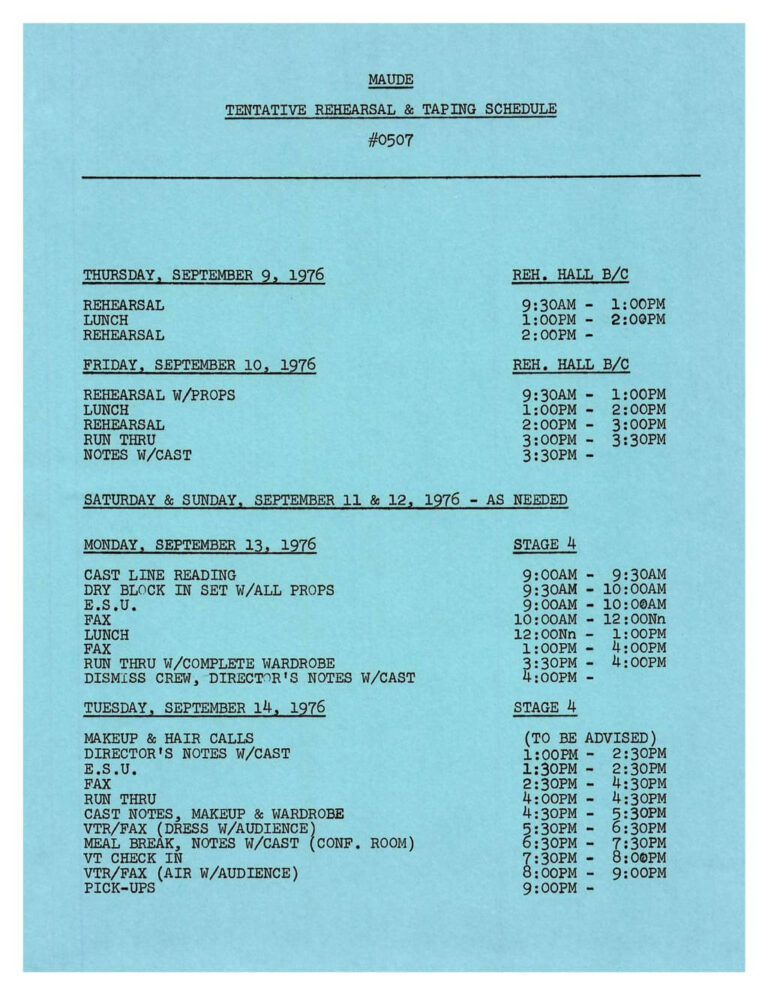

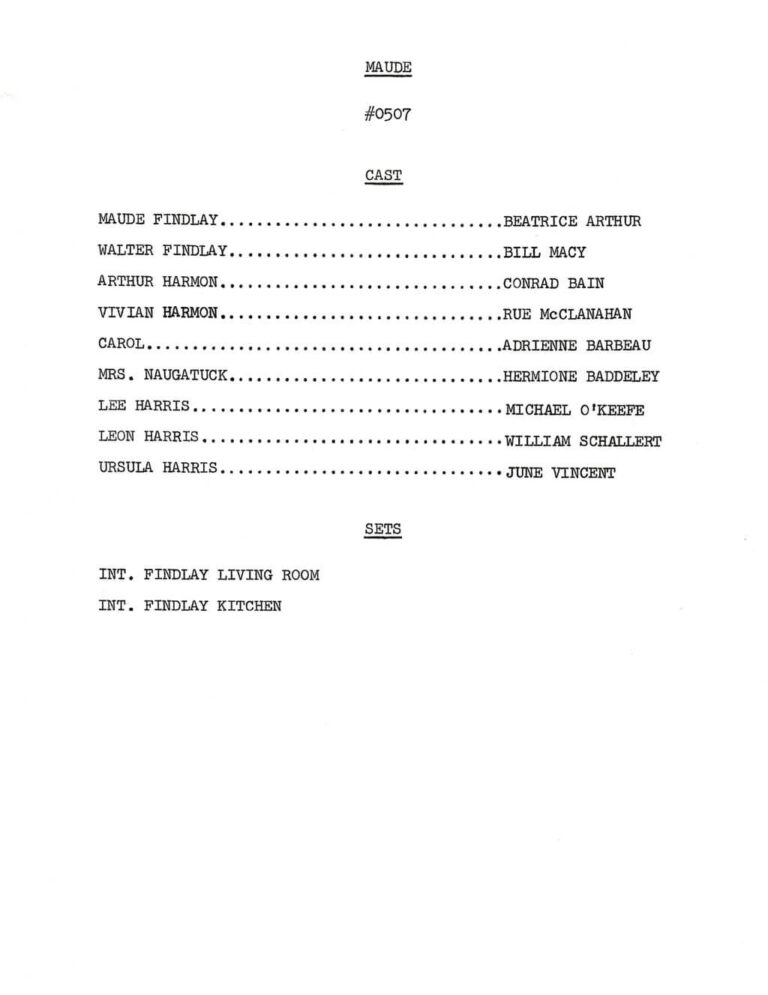

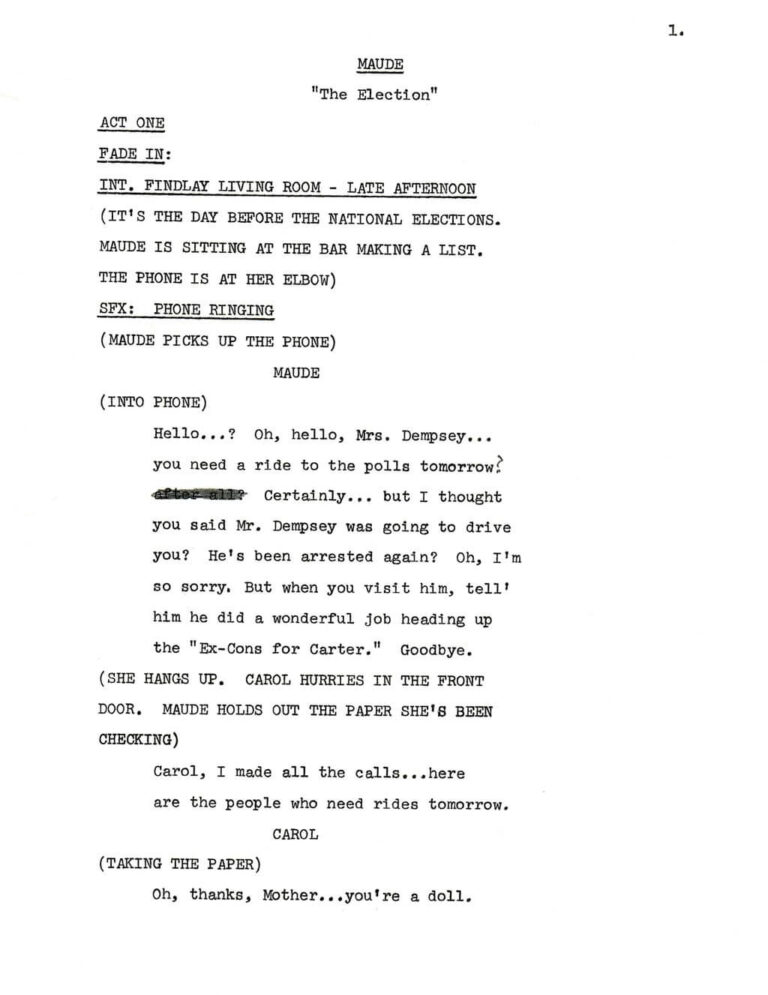

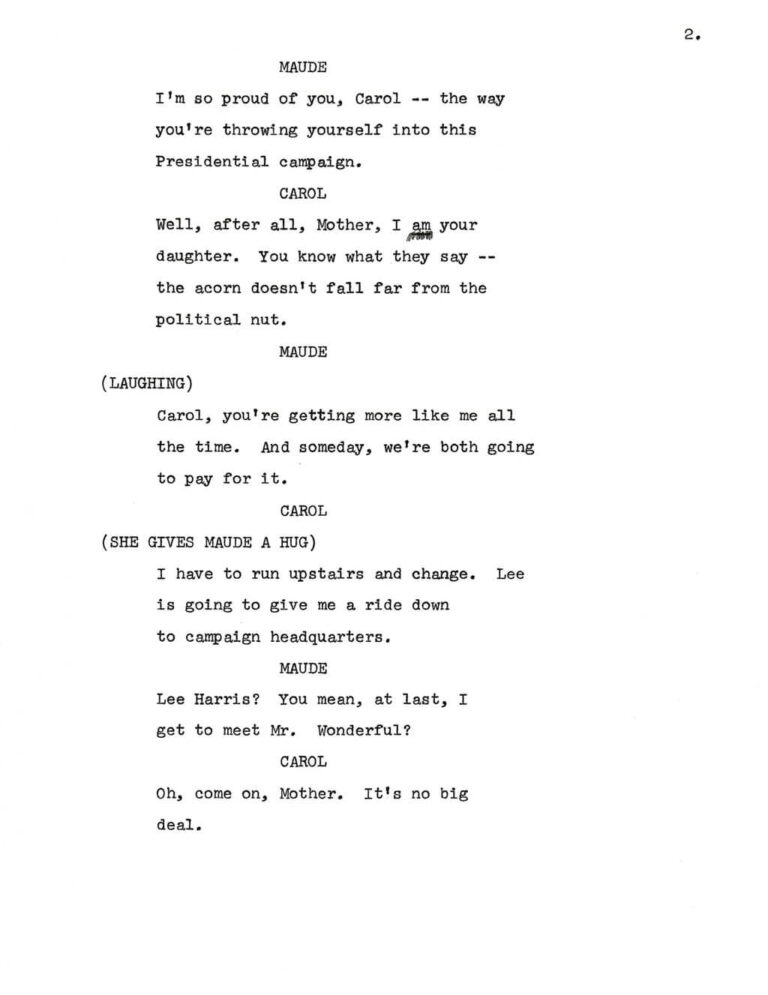

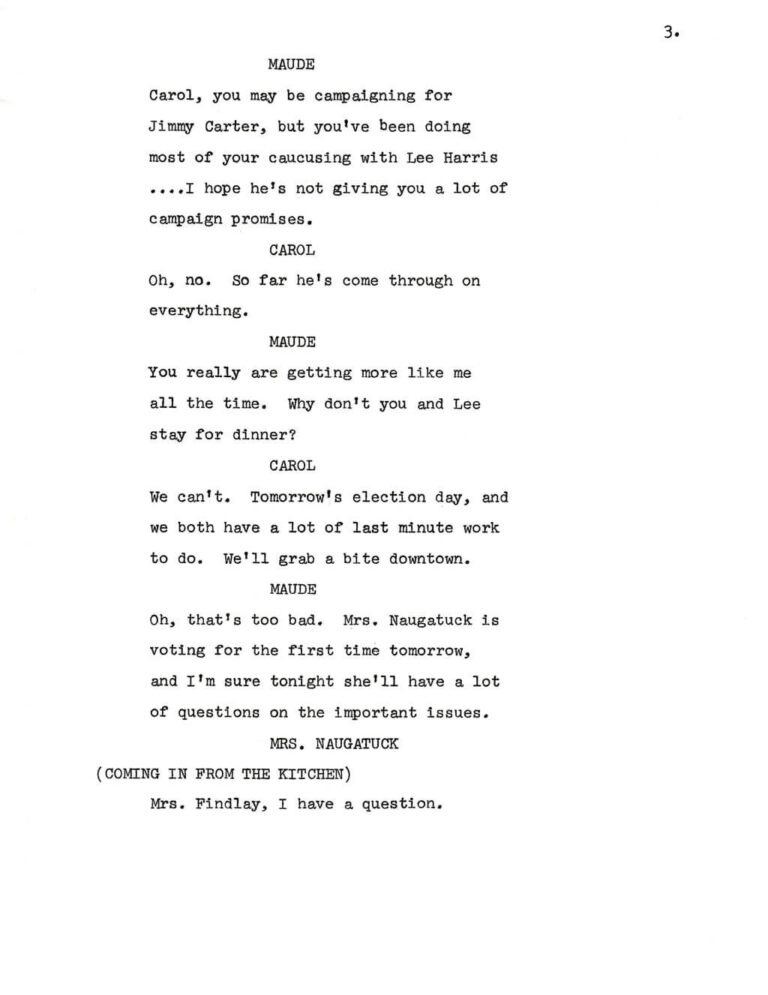

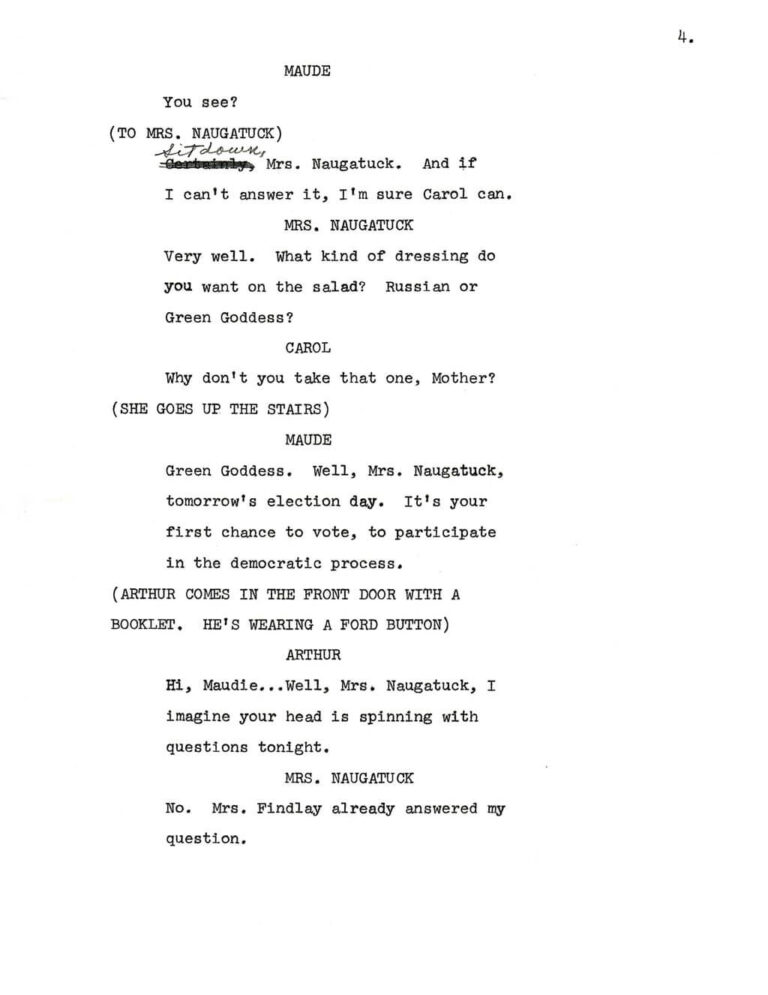

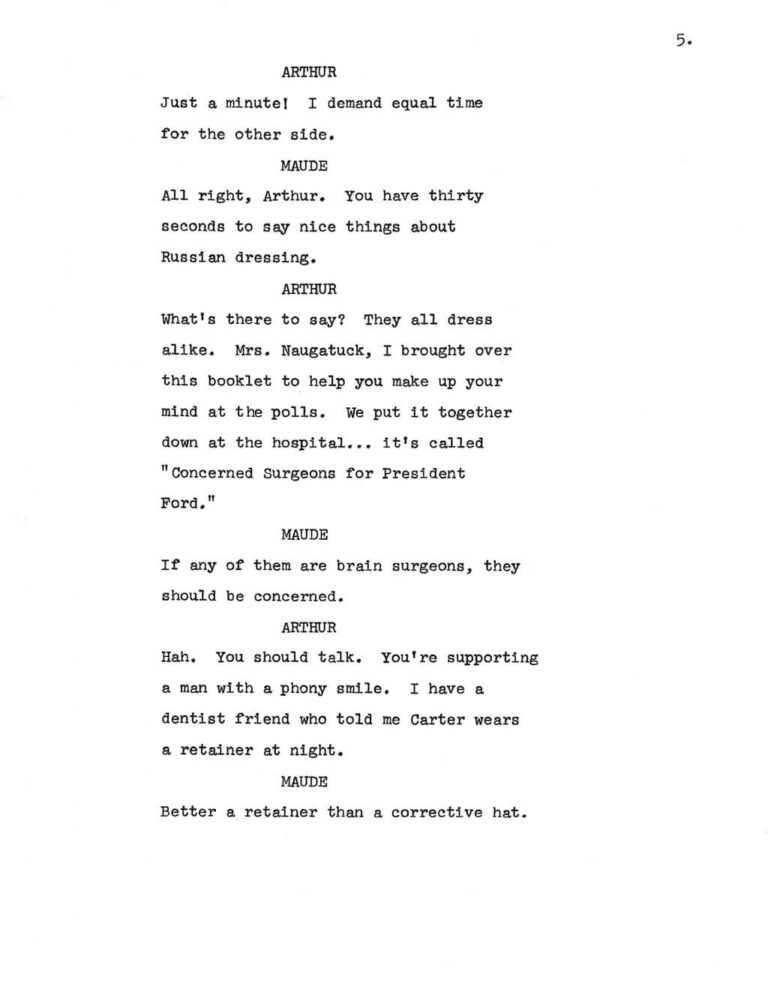

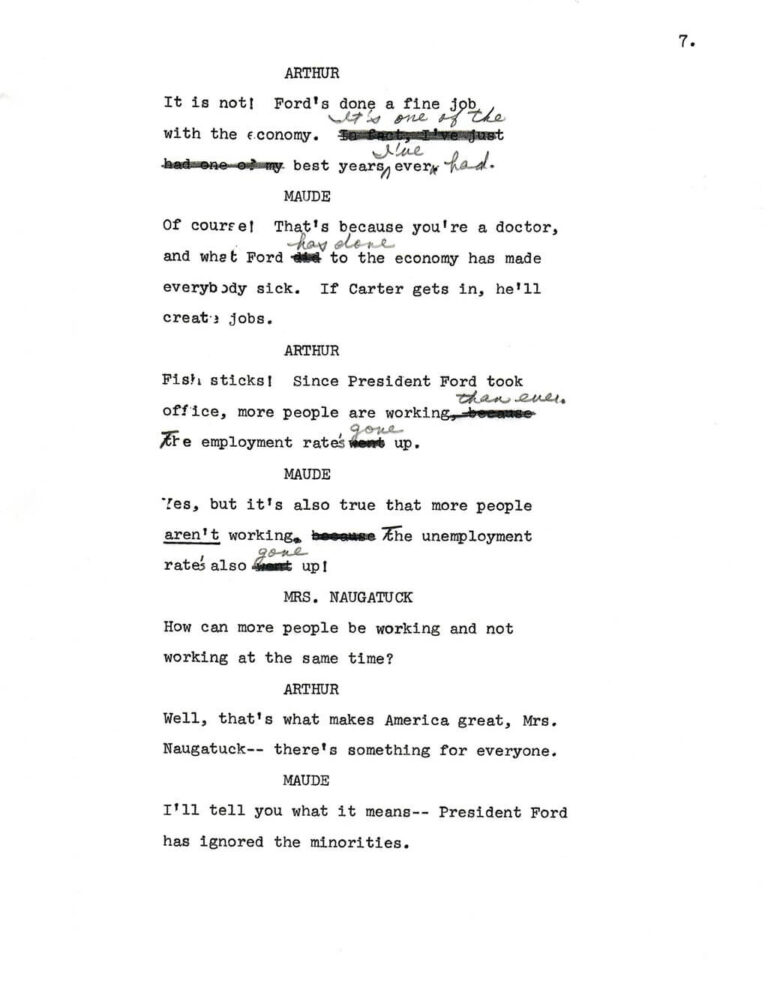

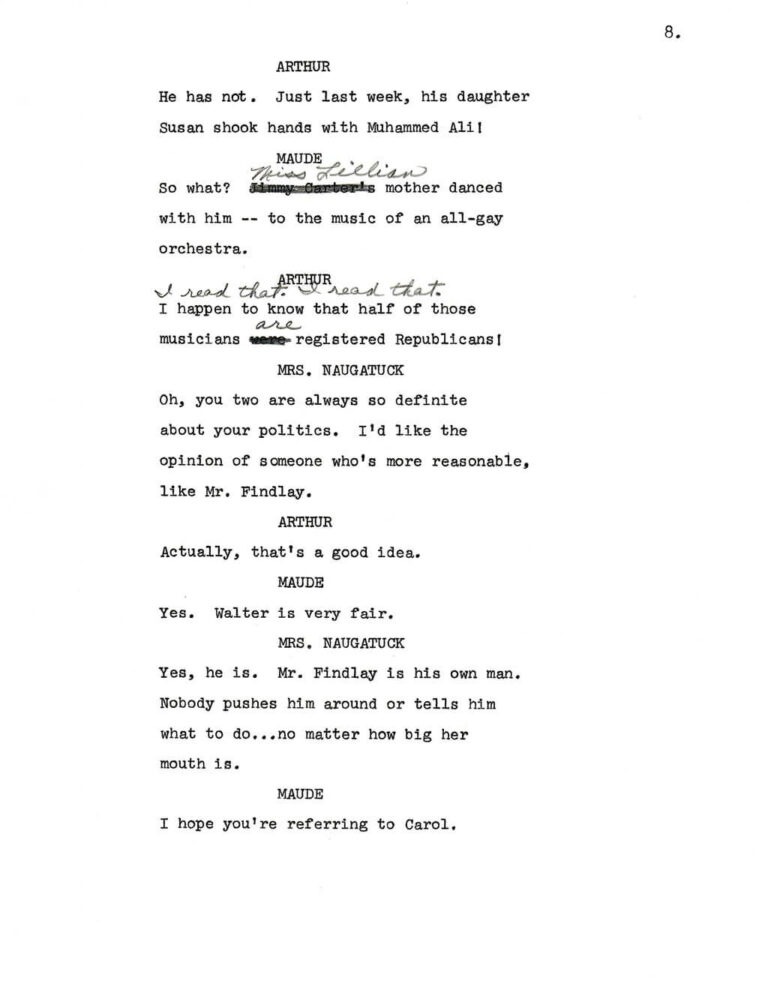

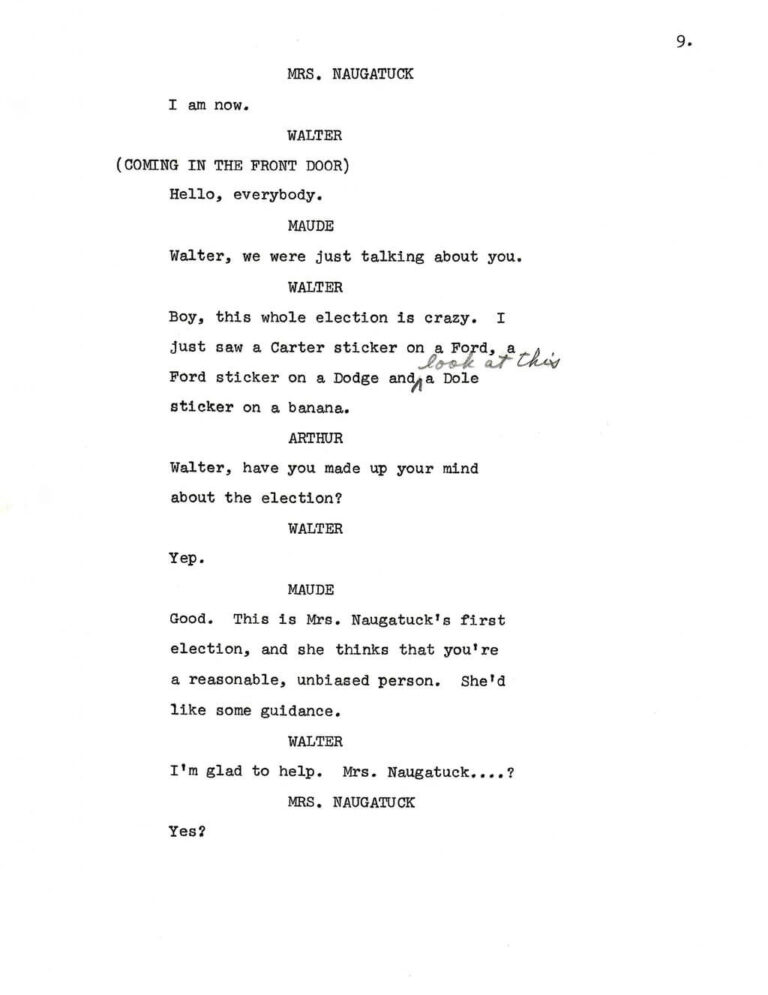

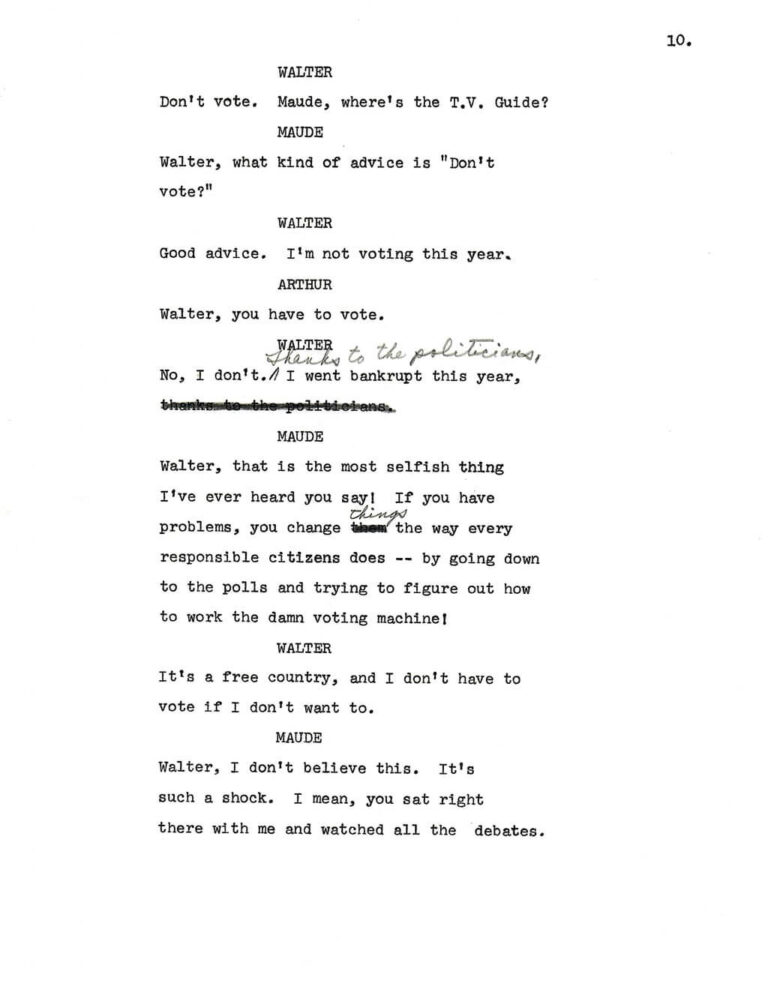

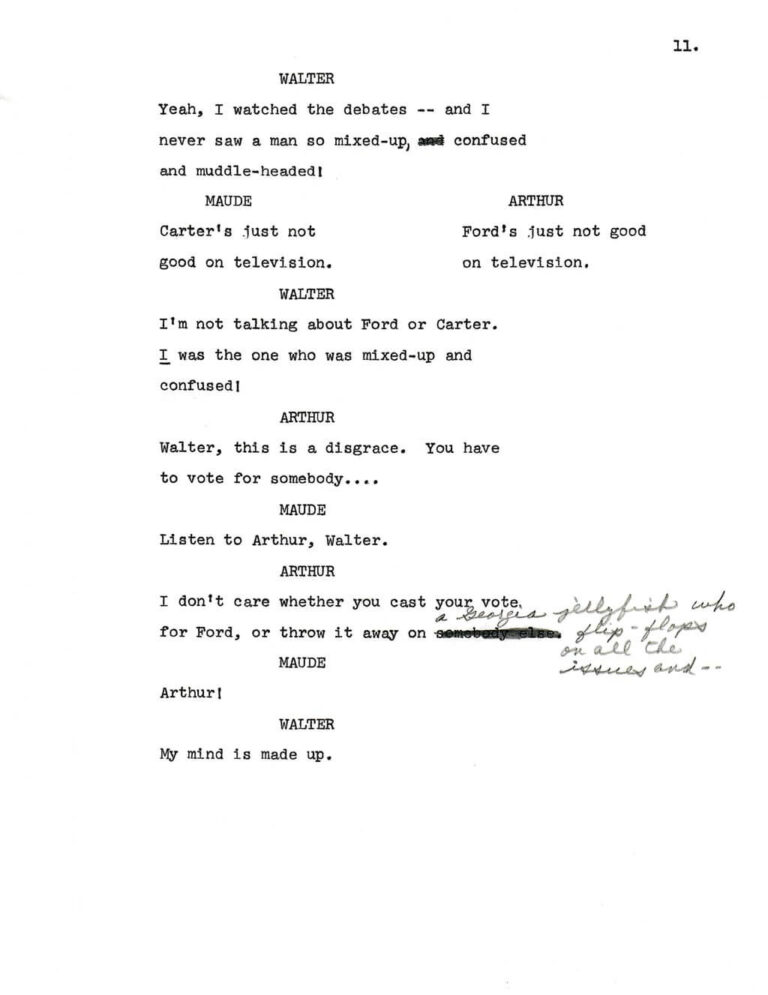

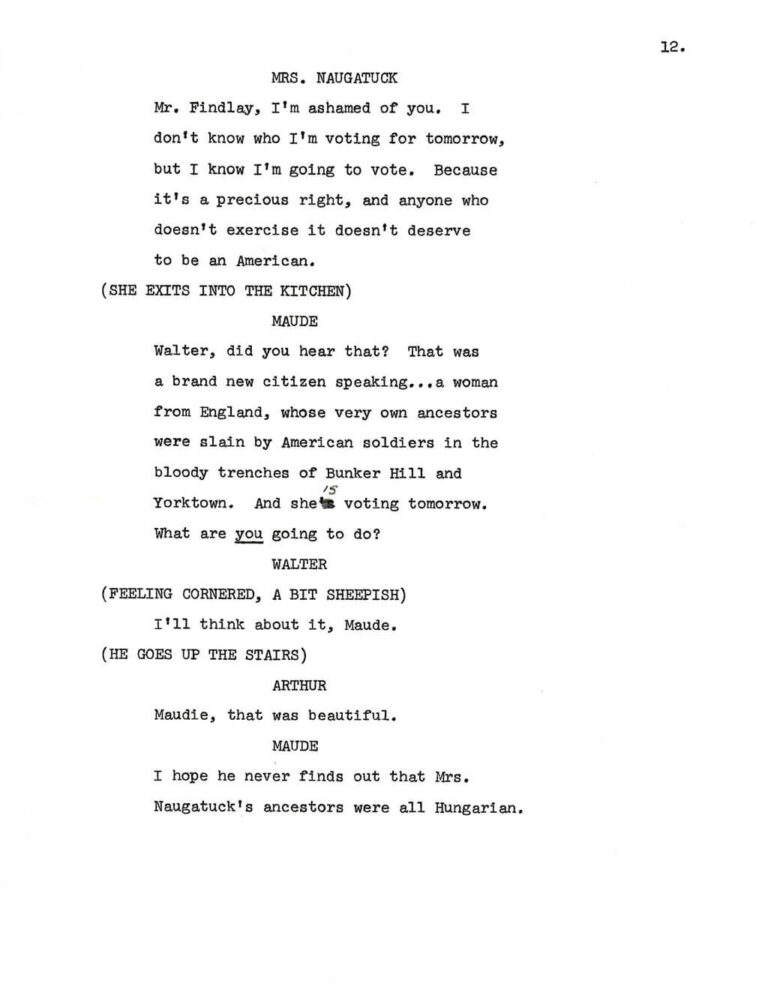

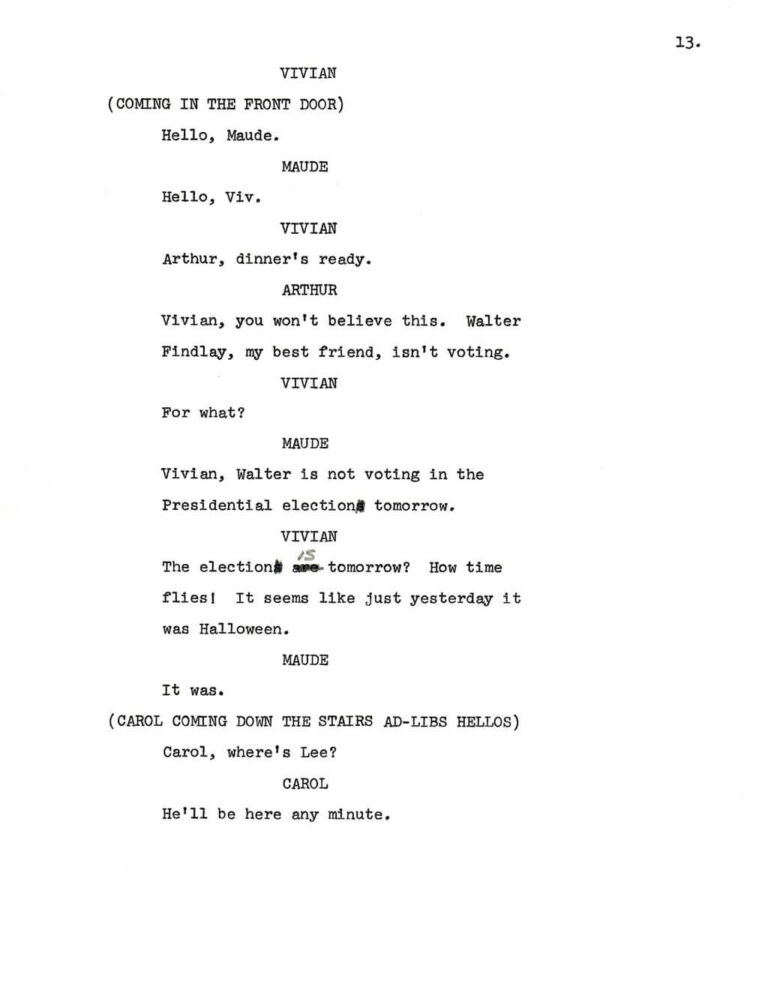

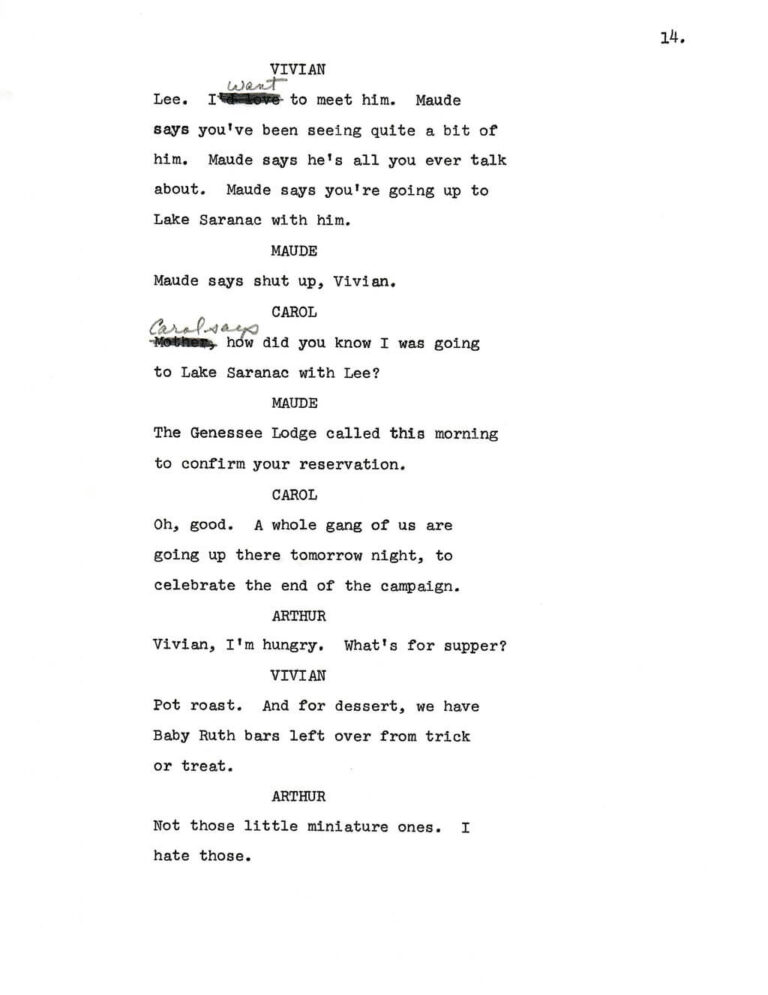

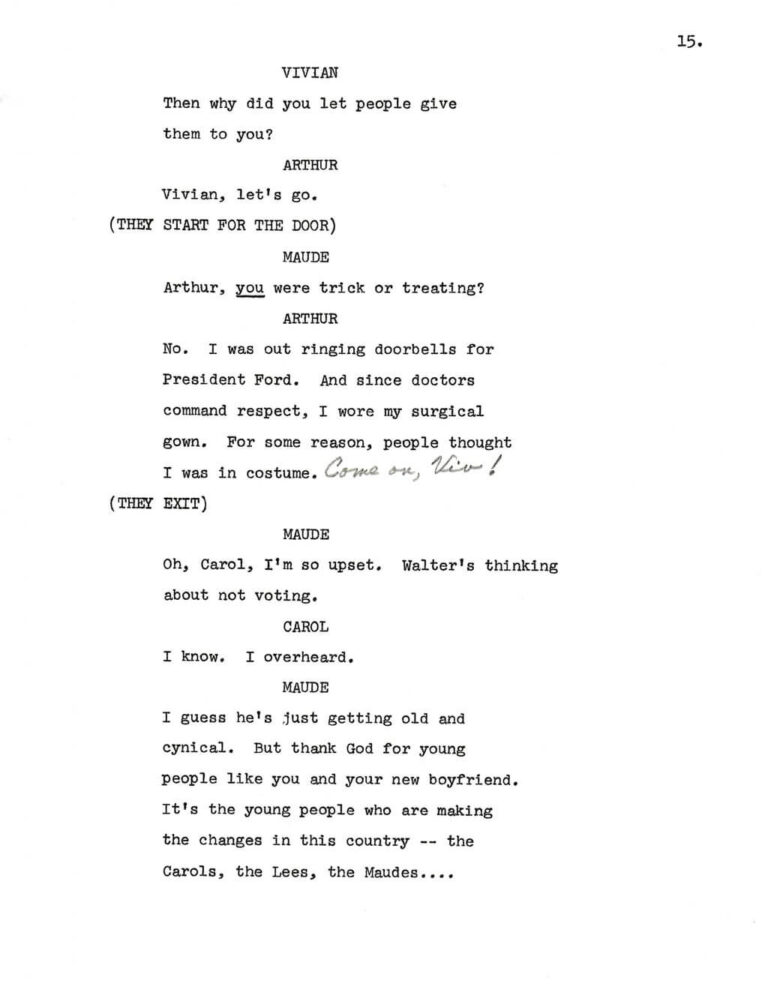

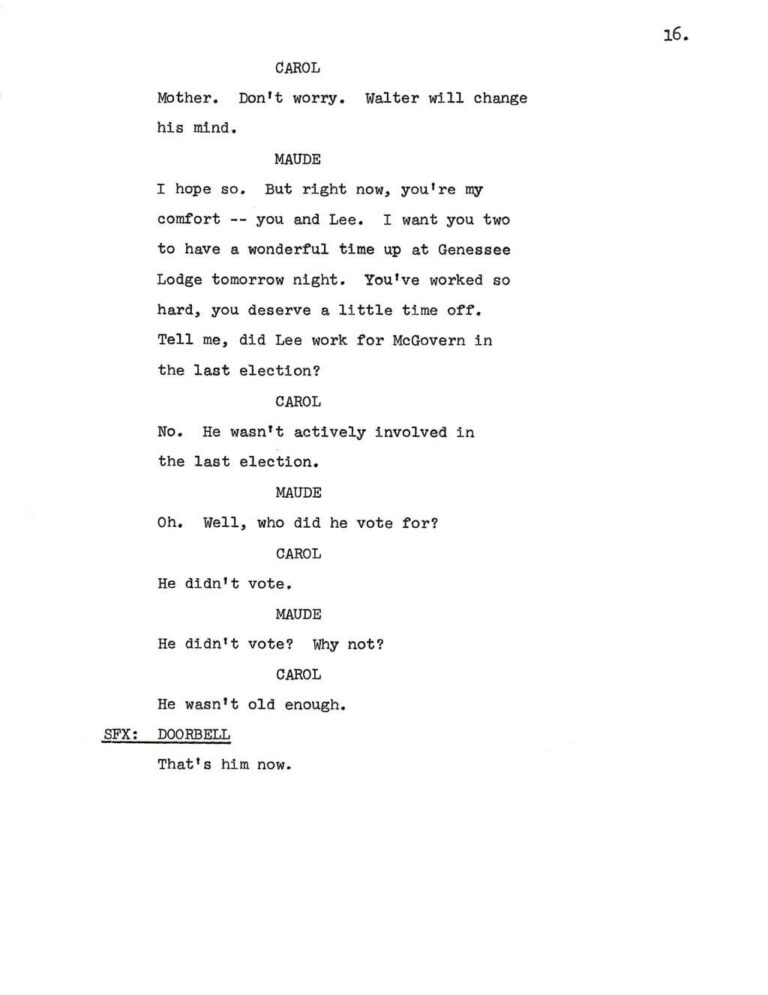

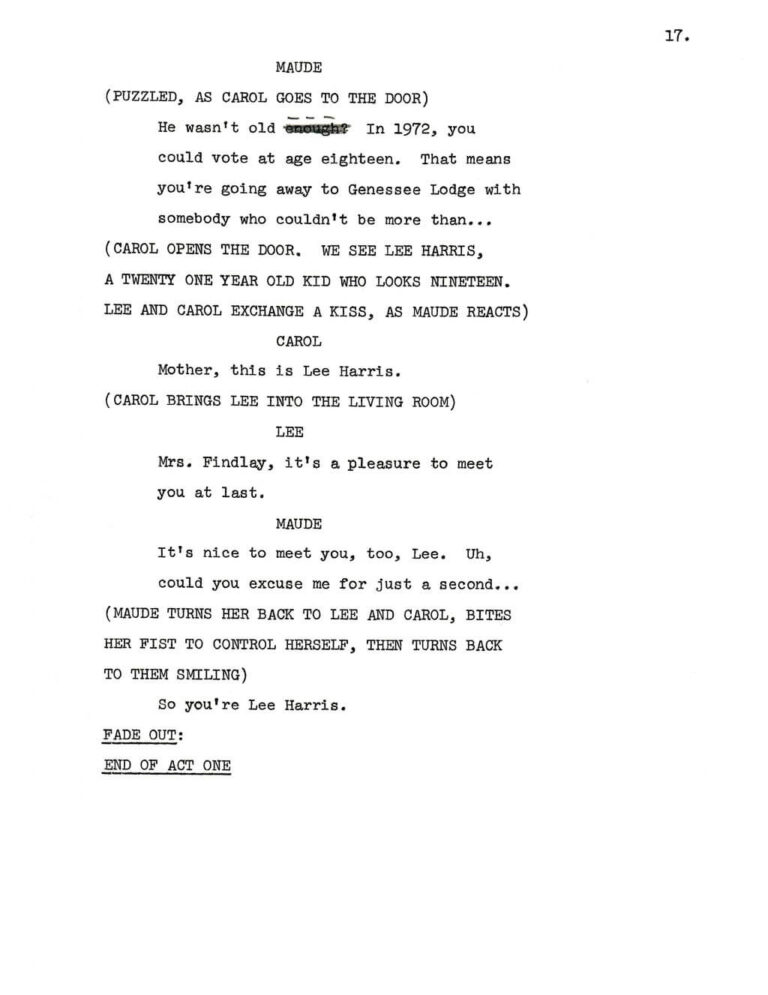

Maude, “The Election,” October 6, 1975

In a fourth season multi-episode arc, Maude mounts a competitive campaign for New York state senate, reveling in the experience of actualizing her personal political ambitions—and seeing her name on an official ballot. The rigors of the campaign, and the thought of uprooting her life to move to the state capital, leave her marriage strained to the point of collapse. Her controversial views cost her the election, so Maude doesn’t actually have to reckon with a choice between political service or home life, but the episode is deft in its portrayal of Maude as a competent, viable candidate who is also fighting against deep ideological pressures to stay at home. Maude’s deferred dreams are ultimately realized in a neat gesture of vindication when the series finale finds her heading to Washington to serve as a United States congressperson.

Maude (1972-1978, CBS) starred Bea Arthur as outspoken feminist Maude Findlay, an indomitable and ambitious woman sharing a suburban home with her fourth husband, Walter (Bill Macy) and adult daughter, Carol (Adrienne Barbeau). The show made history with its unflinching treatment of issues like abortion, divorce, menopause, alcoholism, and mental health.

Maude, “The Election”

Original air date: October 6, 1975

Written by Norman Lear and Charlie Hauck

Directed by Hal Cooper

Featuring Bea Arthur, Bill Macy, and Adrienne Barbeau

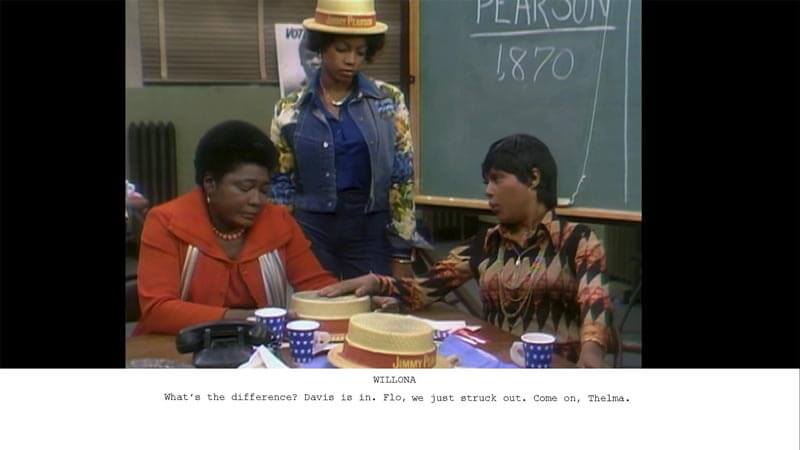

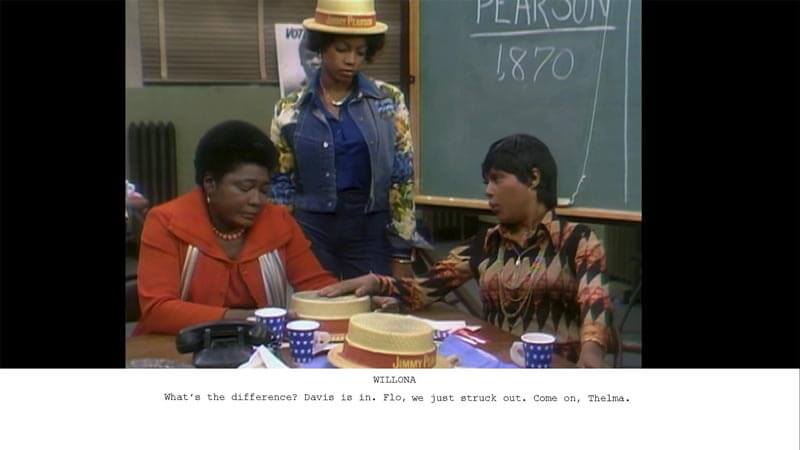

Good Times, “The Politicians,” November 4, 1975

Norman Lear’s body of work promoted his belief that the democratic experiment requires coexistence as communities, neighbors, and families connected in pursuit of a common good. In this episode of Good Times, the Evans family comes together to campaign for a mayoral race… even though they are split on which candidate to back. Florida and James are models of engaged citizenship for their three children, who chip in by stuffing mailers and distributing posters, and step up to energetically debate the merits of the opposing candidates alongside their parents. (J. J. Evans thinks his candidate is “Dy-No-Mite.”) When Florida’s preferred candidate loses the election, everyone involved comes together to agree that low voter turnout in the community is a problem to be solved next election season—no matter whom those absent voters might back.

Good Times (1974-1979, CBS) starred Esther Rolle and John Amos as Florida and James Evans, working parents raising three children in the Chicago projects. During the 1974-75 season, Good Times was one of five Lear-created sitcoms in the Nielsen top ten, and, along with The Jeffersons and Sanford and Son, one of three to focus on Black family life.

Good Times, “The Politicians”

Original air date: November 4, 1975

Written by Jack Elinson and Norman Paul

Directed by Herbert Kenwith

Featuring Esther Rolle, John Amos, BernNadette Stanis, Ja’Net DuBois, and Stanley Clay

Sanford and Son, “Strange Bedfellows,” January 24, 1975

Norman Lear’s sitcoms self-consciously wove campaigning, canvassing, and voting into the everyday texture of their storyworlds. In doing so, they invited their vast audience to consider their own roles in the political life of their communities, and their country—and to recognize that regular people have the capacity to make real change. Lamont Sanford doesn’t intend to involve himself in the political arena, but his friends and neighbors recognize the value of his intellect, his charisma, and his awareness of the issues. With the encouragement of the community, he agrees to make a run as a state assemblyman. Lamont’s impassioned approach to the issues facing his community—like gentrification and consumer fraud—run afoul of his father’s more self-serving attitudes, including his fear that Lamont will move away and abandon the family junk business.

Sanford and Son (1972-1977, NBC) starred Redd Foxx as the curmudgeonly widower Fred Sanford and Demond Wilson as Lamont, his son and partner in a junk-dealing business in the South Central Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts. It was the highest-rated half-hour in the history of the NBC network at the time of its airing (second only to Lear’s own All In the Family on CBS) and rated in the Nielsen top ten for five of its six seasons.

Sanford and Son, “Strange Bedfellows”

Original air date: January 24, 1975

Written by Ted Bergman

Directed by Norman Abbott

Featuring Redd Foxx, Demond Wilson and Ed Cambridge

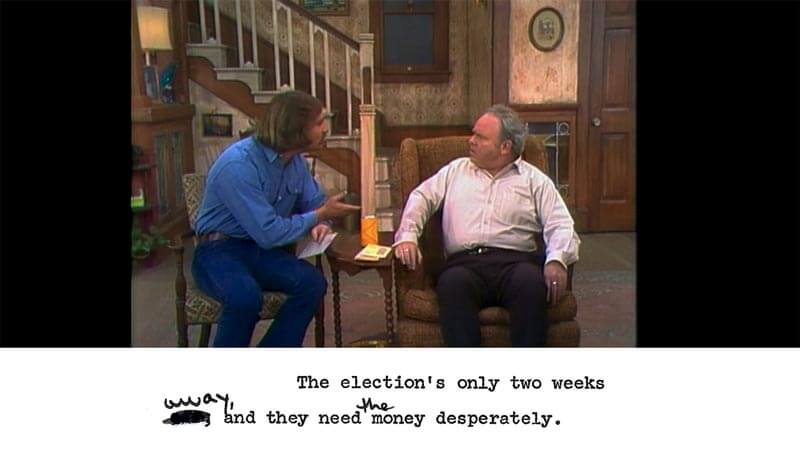

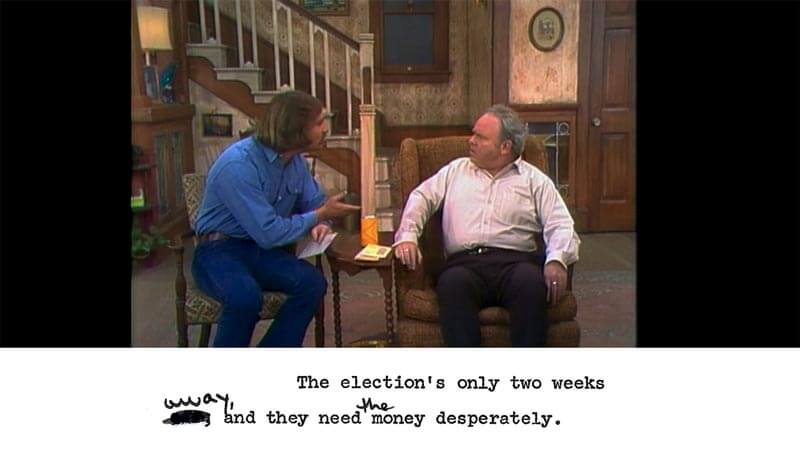

All In the Family, “Mike Comes into Money,” November 4, 1972

All in the Family had a series-long investment in modeling the democratic process and shoring up the political competency of its audience, especially when it came to making participation in politics appear accessible to everyday Americans in their own communities. In this episode, which aired three days before the 1972 Presidential contest between incumbent Richard Nixon and senator George McGovern, Mike (“Meathead” to Archie) inherits a small sum of money and decides to donate the bulk of it to McGovern’s under resourced campaign. Archie is incensed; he is owed rent money and considers a political donation a squandering of good money. Mike explains that, from his point of view, supporting a campaign he believes in is the surest investment in his family and his community.

All in the Family (1971-1979, CBS) starred Carroll O’Connor as Archie Bunker, an irascible, opinionated blue-collar conservative who lords over a home shared with his long-suffering wife, Edith (Jean Stapleton), daughter (Sally Struthers), and outspoken liberal son-in-law “Meathead” (Rob Reiner). The show won 22 Emmy awards and is among the most influential comedy series of all time, infusing network television with realism, topicality, and controversy that would alter the medium’s course.

All In the Family, “Mike Comes into Money”

Original air date: November 4, 1972

Written by Michael Ross and Bernie West

Directed by John Rich

Featuring Carroll O’Connor, Jean Stapleton, Sally Struthers and Rob Reiner

Maude, “Maude’s Big Move, Parts 1-3,” April 8-22, 1978

Maude was, ultimately, a series that was all about yoking the power of comedy to the urgency of politics. The show was often an interlocutor with current events of national importance during the civil rights era, most prominently including the second-wave feminist movement. Lear faced off with networks, censors, and cultural gatekeepers across the country to ensure that hard-hitting dialogues about real issues facing everyday Americans were represented on television, including a remarkable battle waged to air an episode in which Maude made a carefully considered decision to have an abortion…some three months before the passage of Roe v. Wade. It was a fitting conclusion to Maude Findlay’s story to find her walking the halls of Congress as a newly minted representative from the state of New York, ever-unphased in her resolve to speak her mind and make a difference.

Maude (1972-1978, CBS) starred Bea Arthur as outspoken feminist Maude Findlay, an indomitable and ambitious woman sharing a suburban home with her fourth husband, Walter (Bill Macy) and adult daughter, Carol (Adrienne Barbeau). The show made history with its unflinching treatment of issues like abortion, divorce, menopause, alcoholism, and mental health.

Maude, “Maude’s Big Move: Part 3”

Original air date: April 22, 1978

Written by Charlie Hauck, William Davenport, Arthur Julian, and Rod Parker

Directed by Hal Cooper

Featuring Bea Arthur and Bill Macy

Sanford and Son, “Committee Man,” November 12, 1976

When Fred Sanford is appointed to serve on a mayor’s committee in this episode of Sanford and Son, he finds that he relishes his newfound power to make decisions impacting his community. However, his basest instincts are tested when a slumlord offers him a tempting bribe in exchange for his vote. Lamont intervenes, and Fred makes the right decision, but only after coming to a harsh realization about how corruptible politicians can truly compromise the wellbeing of their constituents. Like many of Lear’s characters, Fred Sanford is a complex and sometimes unenviable figure, but he finds his imperfect way past self-interest and personal gain to develop a respect for the sacred trust of those he has been charged to represent.

Sanford and Son (1972-1977, NBC) starred Redd Foxx as the curmudgeonly widower Fred Sanford and Demond Wilson as Lamont, his son and partner in a junk-dealing business in the South Central Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts. It was the highest-rated half-hour in the history of the NBC network at the time of its airing (second only to Lear’s own All In the Family on CBS) and rated in the Nielsen top ten for five of its six seasons.

Sanford and Son, “Committee Man”

Original air date: November 12, 1976

Written by Garry Shandling

Directed by Chuck Liotta

Featuring Redd Foxx and Demond Wilson

Choose a Clip

All In the Family, “The Election Story,” October 30, 1971 – 1

Much of All in the Family‘s narrative propulsion stems from a deep political rift that divides the Bunker household: Archie is a confident conservative, his daughter and son-in-law are outspoken liberals, and his wife, Edith, quietly attempts impartiality. Like many American families, the Bunkers find themselves clashing on any number of issues due to generational differences, gender differences, educational levels, and attitudes borne of disparate life experiences. In this episode, Archie balks when Gloria invites liberal candidate Claire Packer into his home, but Gloria turns the tables when she chastises her father for not actually exercising his right to vote. As was explained in an on-screen disclaimer before the earliest national broadcasts of All in the Family, Lear’s charge with this series was to use humor to deconstruct the complexities of Archie Bunker’s attitudes and opinions: “By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show—in a mature fashion—just how absurd they are.”

All in the Family (1971-1979, CBS) starred Carroll O’Connor as Archie Bunker, an irascible, opinionated blue-collar conservative who lords over a home shared with his long-suffering wife, Edith (Jean Stapleton), daughter (Sally Struthers), and outspoken liberal son-in-law “Meathead” (Rob Reiner). The show won 22 Emmy awards and is among the most influential comedy series of all time, infusing network television with realism, topicality, and controversy that would alter the medium’s course.

All In the Family, “The Election Story,” October 30, 1971 – 2

While most sitcoms find narrative closure in a neat wrap-up before the end credits roll, Lear’s shows were comfortable with unsettled issues, characters who wavered, and conflicts that didn’t lead to resolutions. In this episode, Archie confidently spouts political opinions but is chagrined when he arrives at his neighborhood polling place and finds himself unregistered…and therefore ineligible to vote. With characteristic arrogance, he attempts to persuade Edith to cast her vote on his behalf, but she staunchly upholds her right to equal participation and casts her vote for the opposition. Archie slumps in silent humiliation as the episode fades, realizing the futility of soliloquizing about politics without actually participating in the democratic process.

All in the Family (1971-1979, CBS) starred Carroll O’Connor as Archie Bunker, an irascible, opinionated blue-collar conservative who lords over a home shared with his long-suffering wife, Edith (Jean Stapleton), daughter (Sally Struthers), and outspoken liberal son-in-law “Meathead” (Rob Reiner). The show won 22 Emmy awards and is among the most influential comedy series of all time, infusing network television with realism, topicality, and controversy that would alter the medium’s course.

Maude, “The Election,” October 6, 1975

In a fourth season multi-episode arc, Maude mounts a competitive campaign for New York state senate, reveling in the experience of actualizing her personal political ambitions—and seeing her name on an official ballot. The rigors of the campaign, and the thought of uprooting her life to move to the state capital, leave her marriage strained to the point of collapse. Her controversial views cost her the election, so Maude doesn’t actually have to reckon with a choice between political service or home life, but the episode is deft in its portrayal of Maude as a competent, viable candidate who is also fighting against deep ideological pressures to stay at home. Maude’s deferred dreams are ultimately realized in a neat gesture of vindication when the series finale finds her heading to Washington to serve as a United States congressperson.

Maude (1972-1978, CBS) starred Bea Arthur as outspoken feminist Maude Findlay, an indomitable and ambitious woman sharing a suburban home with her fourth husband, Walter (Bill Macy) and adult daughter, Carol (Adrienne Barbeau). The show made history with its unflinching treatment of issues like abortion, divorce, menopause, alcoholism, and mental health.

Good Times, “The Politicians,” November 4, 1975

Norman Lear’s body of work promoted his belief that the democratic experiment requires coexistence as communities, neighbors, and families connected in pursuit of a common good. In this episode of Good Times, the Evans family comes together to campaign for a mayoral race… even though they are split on which candidate to back. Florida and James are models of engaged citizenship for their three children, who chip in by stuffing mailers and distributing posters, and step up to energetically debate the merits of the opposing candidates alongside their parents. (J. J. Evans thinks his candidate is “Dy-No-Mite.”) When Florida’s preferred candidate loses the election, everyone involved comes together to agree that low voter turnout in the community is a problem to be solved next election season—no matter whom those absent voters might back.

Good Times (1974-1979, CBS) starred Esther Rolle and John Amos as Florida and James Evans, working parents raising three children in the Chicago projects. During the 1974-75 season, Good Times was one of five Lear-created sitcoms in the Nielsen top ten, and, along with The Jeffersons and Sanford and Son, one of three to focus on Black family life.

Sanford and Son, “Strange Bedfellows,” January 24, 1975

Norman Lear’s sitcoms self-consciously wove campaigning, canvassing, and voting into the everyday texture of their storyworlds. In doing so, they invited their vast audience to consider their own roles in the political life of their communities, and their country—and to recognize that regular people have the capacity to make real change. Lamont Sanford doesn’t intend to involve himself in the political arena, but his friends and neighbors recognize the value of his intellect, his charisma, and his awareness of the issues. With the encouragement of the community, he agrees to make a run as a state assemblyman. Lamont’s impassioned approach to the issues facing his community—like gentrification and consumer fraud—run afoul of his father’s more self-serving attitudes, including his fear that Lamont will move away and abandon the family junk business.

Sanford and Son (1972-1977, NBC) starred Redd Foxx as the curmudgeonly widower Fred Sanford and Demond Wilson as Lamont, his son and partner in a junk-dealing business in the South Central Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts. It was the highest-rated half-hour in the history of the NBC network at the time of its airing (second only to Lear’s own All In the Family on CBS) and rated in the Nielsen top ten for five of its six seasons.

All In the Family, “Mike Comes into Money,” November 4, 1972

All in the Family had a series-long investment in modeling the democratic process and shoring up the political competency of its audience, especially when it came to making participation in politics appear accessible to everyday Americans in their own communities. In this episode, which aired three days before the 1972 Presidential contest between incumbent Richard Nixon and senator George McGovern, Mike (“Meathead” to Archie) inherits a small sum of money and decides to donate the bulk of it to McGovern’s under resourced campaign. Archie is incensed; he is owed rent money and considers a political donation a squandering of good money. Mike explains that, from his point of view, supporting a campaign he believes in is the surest investment in his family and his community.

All in the Family (1971-1979, CBS) starred Carroll O’Connor as Archie Bunker, an irascible, opinionated blue-collar conservative who lords over a home shared with his long-suffering wife, Edith (Jean Stapleton), daughter (Sally Struthers), and outspoken liberal son-in-law “Meathead” (Rob Reiner). The show won 22 Emmy awards and is among the most influential comedy series of all time, infusing network television with realism, topicality, and controversy that would alter the medium’s course.

Maude, “Maude’s Big Move, Parts 1-3,” April 8-22, 1978

Maude was, ultimately, a series that was all about yoking the power of comedy to the urgency of politics. The show was often an interlocutor with current events of national importance during the civil rights era, most prominently including the second-wave feminist movement. Lear faced off with networks, censors, and cultural gatekeepers across the country to ensure that hard-hitting dialogues about real issues facing everyday Americans were represented on television, including a remarkable battle waged to air an episode in which Maude made a carefully considered decision to have an abortion…some three months before the passage of Roe v. Wade. It was a fitting conclusion to Maude Findlay’s story to find her walking the halls of Congress as a newly minted representative from the state of New York, ever-unphased in her resolve to speak her mind and make a difference.

Maude (1972-1978, CBS) starred Bea Arthur as outspoken feminist Maude Findlay, an indomitable and ambitious woman sharing a suburban home with her fourth husband, Walter (Bill Macy) and adult daughter, Carol (Adrienne Barbeau). The show made history with its unflinching treatment of issues like abortion, divorce, menopause, alcoholism, and mental health.

Sanford and Son, “Committee Man,” November 12, 1976

When Fred Sanford is appointed to serve on a mayor’s committee in this episode of Sanford and Son, he finds that he relishes his newfound power to make decisions impacting his community. However, his basest instincts are tested when a slumlord offers him a tempting bribe in exchange for his vote. Lamont intervenes, and Fred makes the right decision, but only after coming to a harsh realization about how corruptible politicians can truly compromise the wellbeing of their constituents. Like many of Lear’s characters, Fred Sanford is a complex and sometimes unenviable figure, but he finds his imperfect way past self-interest and personal gain to develop a respect for the sacred trust of those he has been charged to represent.

Sanford and Son (1972-1977, NBC) starred Redd Foxx as the curmudgeonly widower Fred Sanford and Demond Wilson as Lamont, his son and partner in a junk-dealing business in the South Central Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts. It was the highest-rated half-hour in the history of the NBC network at the time of its airing (second only to Lear’s own All In the Family on CBS) and rated in the Nielsen top ten for five of its six seasons.

Though tapping into pop culture to motivate political action is commonplace today, it was not always. The shows Norman Lear created were unprecedented (and unreplicated) weekly mass cultural events, and his commitment to ensuring that civic engagement was a driving message of some of the most-viewed entertainment programming of the American 20th century was no small gesture.

Lear well understood the power of comedy to open minds and level playing fields, and he reveled in a certain sort of laughter that came at the shock of self-recognition. His humor was about our common humanity, and our shared future. In an unpublished editorial, Lear reflected on what it was that really made his art matter: “I am convinced that there are millions of thoughtful Americans who are enormously frustrated by what they see and cannot see on television. I think we matter if we talk to each other about it. I think we matter if we talk to our children about it. I think we matter if we write about it. There are a million things one can do if you just believe in raising your hand and saying something matters. I believe in my heart it matters.”

From a unique vantage entering his second century of American citizenship, Norman Lear used the occasion of his 100th birthday to passionately remind us that the democratic promise is a fragile one, and that our votes are the only mechanism for guaranteeing that our fundamental rights are renewed, election over election for generations. “Let us renew a patriotism of purpose,” Lear reflected, “of caring for one another and for our democracy. Building a shared future will always be our task. Taking the long view, I believe we can still be ‘a more perfect union.'”